May 27, 2025

By Julia Beeson

The legacy of Hilma af Klint, a visionary Swedish artist and mother of western abstractionism, has become the center of a commercial, legal and philosophical dispute within the Hilma af Klint Foundation (the Foundation). Originally established to preserve her work and spiritual vision, the Foundation is now divided over how her art should be commercialized, managed, and made accessible. At the heart of the conflict is the fFoundation’s current chair Erik af Klint, his fellow board of directors, and a collapsed deal with gallery David Zwirner. This dispute has not only led to the loss of high-profile collaborations but also raises broader questions about the governance of artistic legacies, the laws governing foundations, and the wider implications of dysfunctional boards.

I. Hilma af Klint

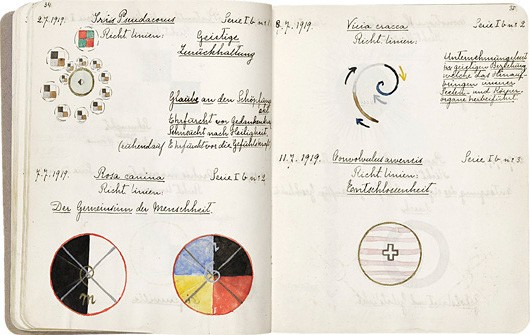

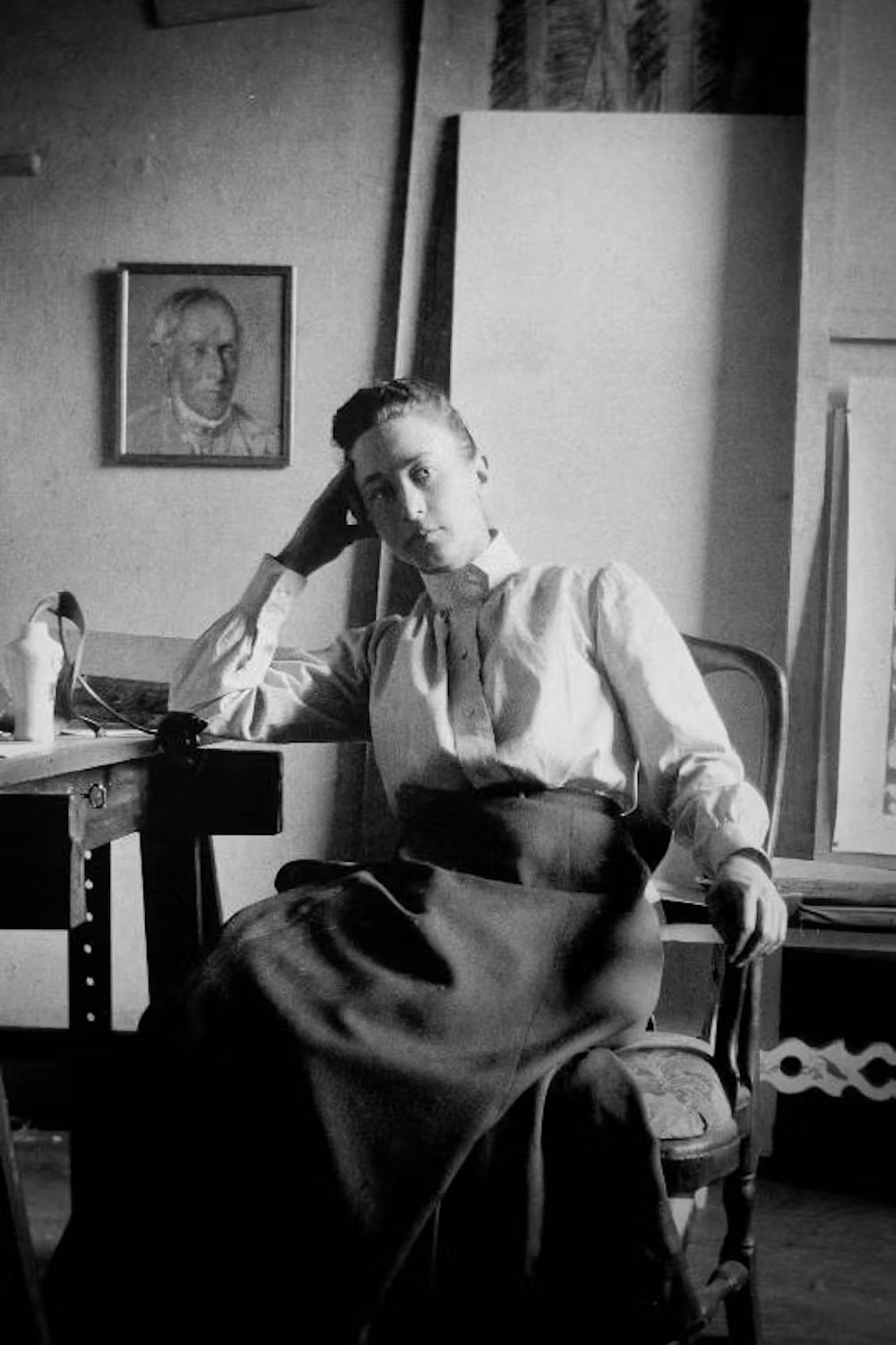

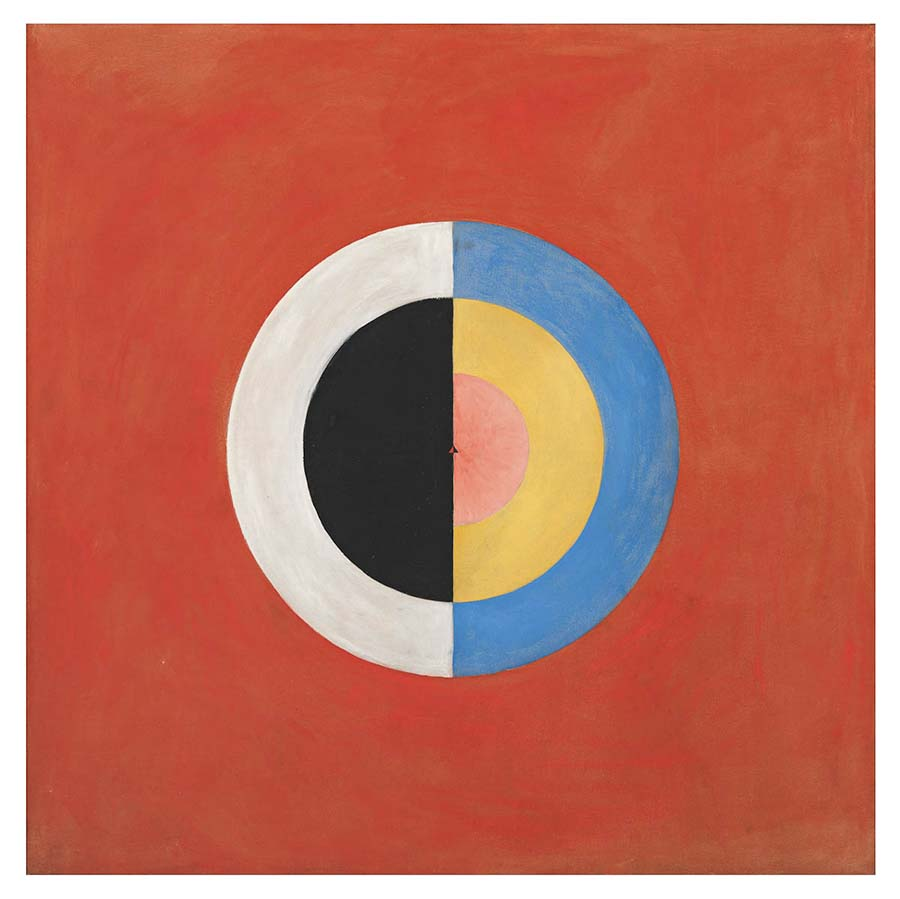

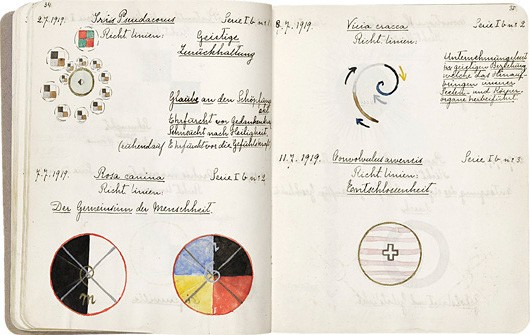

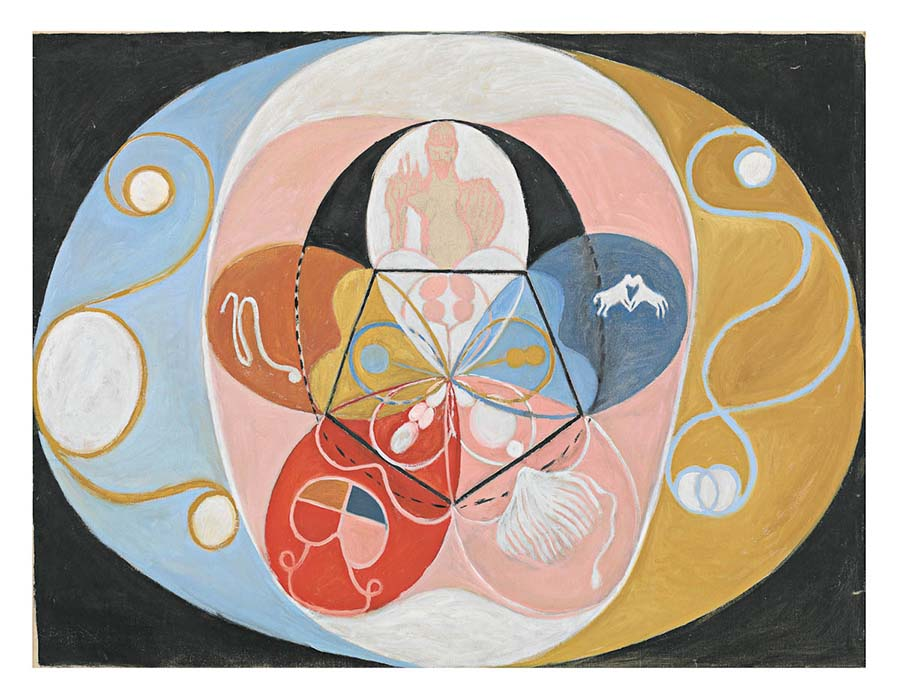

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) was a Swedish artist and painter, who has been recognized as the “true pioneer” of abstract art in the West with her bold, “radically abstract” paintings filled with enigmatic and colorful shapes. Though she was not popular during her time, Af Klint has garnered international recognition as the “true pioneer” of abstract art in the West, as her works were made decades before Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, and Wassily Kandinsky. Another distinctive element of af Klint’s works are that they are largely inspired by her spirituality, drawing from the occultist and esoteric teachings of theosophy and anthroposophy. She even claimed that some of her paintings, most notably The Paintings for the Temple (YEAR) were not painted by herself, but commissioned and even drawn by high spiritual beings, using her as a vessel and working “through her.”

Due to the highly spiritual nature and significance of her work, af Klint withheld most of her works from public view, as she was under the impression that the world was not yet ready to see them. In her notebooks, she stated a wish for her works to remain hidden for at least twenty years following her death. Once her works were allowed to be revealed, they only began to garner any notoriety in 1986, when they were featured in a group exhibition in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (“LACMA”). Since then, her paintings have been met with ever increasing popularity, leading to a sharp increase in the market for her work, and various popular exhibitions around the world.

II. The af Klint Foundation

Since af Klint never married or had any children, she left all her paintings and notes to her nephew Erik af Klint. Erik hoped and attempted to donate her works to a museum, but his efforts were continuously rejected. To ensure the works would be kept safe, he established, and subsequently donated everything to, The Hilma af Klint Foundation in 1972. According to The Foundation’s statutes, it was created and is responsible for the preservation of af Klint’s art and her legacy. The Foundation is also responsible for safeguarding and managing her works. To fulfill the purpose outlined in the statutes, they further instruct the foundation’s board to “keep the work available to those who seek spiritual knowledge or who can contribute to fulfilling the mission that Hilma af Klint’s spiritual principles intended.” They also prohibit the sale of works produced between 1906 and 1915 but allow all other works to be sold so long the proceeds are used for the preservation of her works.

Regarding the composition of the board and its membership, the statutes specify that its board must be chaired by a member of the af Klint family while its remaining Trustees are selected by the Stockholm Administrative court from members of the Anthroposophical Society. The foundation’s current chair of the board is af Klint’s great-grandnephew, who, like his great-grandfather, is also named Erik af Klint.

III. Legal duties for Foundation Boards

In Sweden, foundations are governed by The Foundation Act. Under the statute, foundations are to be governed to the provisions written in its deed, and the foundation’s board or administrator bears the responsibility of ensuring that foundation and its members adhere to its provisions. Unless otherwise stated within the deed, the board is also responsible for the investment of foundation assets. Foundation boards are also allowed to participate in business activities, but only if such activities align with the foundation’s purpose.

The act also contains a chapter outlining how foundations are supervised. Aside from a few exceptions, most foundations must be registered with the County Administration board, as the statute grants county governments with “supervisory authority.” It mandates county administrative boards to provide the foundation with “advice and information, along with disciplinary powers if the board or any of its members mismanages or fails to perform their duties. Such powers arise when the board does not permit the county board to make inspections, sue for damages, appoint and apply for the dismissal of board members. The board is also subject to oversight from the Kammarkollegiet, who reviews and approves proposed amendments to the statutes pertaining to the foundation’s purpose, or its board.

IV. Erik af Klint Versus the Board

Previously Erik was uninvolved with the foundation. But since he became its active chair in 2023, the foundation has suffered from various internal conflicts between him and the rest of the board, as seen previously thwarted commercial deals and collaborations. In April 2023, he filed a lawsuit against the other board members and the foundation’s CEO for gross breach of trust, accusing them of violating their fiduciary duties to the foundation by making unauthorized deals for their own profit. He requested that the court allow him to reshuffle the board and cancel the contracts facilitated by the foundation’s CEO, Jessica Höglund.

Tensions between Erik and the board worsened following the proposed and highly anticipated deal between gallerist David Zwirner and The Foundation. David Zwirner owns the David Zwirner gallery, an international contemporary art gallery representing artists and estates in both primary and secondary markets. His gallery has hosted an exhibition of Af Klint’s work—featuring a series of eight previously undiscovered works obtained from a privately owned collection—before facilitating its acquisition to the Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland. According to Zwirner, the proceeds of sale would have been invested into the research, publications, and to preserve the 1,300 pieces that remain under the foundation’s care.

Initially, Erik af Klint appeared to be opposed solely to the deal with Zwirner, citing concerns about the implications of selling individual works that are part of a series. In an interview with The Guardian, Erik af Klint stated regarding the deal that “the paintings connect, and to sell some within a series would interrupt that.” Despite his position imposing a significant roadblock, press teams for Zwirner and the foundation stated that they remained in “advanced discussions” on how to proceed with at least some kind of collaboration in the future.

Unfortunately, any lingering optimism and efforts to collaborate have been seemingly thrashed by a new petition filed by Erik, as well as recent statements made by him and the board which have revealed further disagreement and hostility between them. In February, he filed another petition with the Stockholm District Court in a final attempt to remove the current members of the board, and asked the court to suspend them in the interim until it comes to a decision. This was followed with an interview with Swedish publication Dagens Nyheter, where Erik claimed that af Klint’s work is “not meant to be public,” and should have never been promoted or commodified through by any means. He emphasized that his stance on the matter is “not about what I want, it’s about what the statutes of the foundation dictate” and that all public exhibitions of her work violate the statutes and therefore the Swedish Foundation Act. He has also promised to resign if he fails. Meanwhile, the board’s spokesperson, Varg Gyllander, speaking on behalf of the directors, stated that “[t]he claim that only a select few people may view the art is a gross misinterpretation of the statutes, the will of the founder and Hilma’s intentions.” As of April 3, the court has denied Erik’s request to suspend his fellow board members, so they have retained their positions and are still carrying out their duties—at least for now.

V. Implications

If the board under Erik’s leadership were to follow the statutes according to their text, there would be no public exhibitions, publications, or images of af Klint’s works—they would be placed in a private temple and only be accessible for individuals who “seek spiritual knowledge.” This raises concerns not only for pending or future deals and exhibitions but also current and ongoing collaborations, most notably the Foundation’s current, long-term agreement with the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

Given how disputes between The Foundation’s chair and its remaining directors have already caused wider implicating problems, it is highly likely that we will see a continued pattern of befallen deals and collaboration. The deterioration of the collaboration with David Zwirner and Erik’s call to remove Af Klint’s work from public view is not only a product of their inability to cooperate, but it also highlights how it is imperative for directors to have sufficient clarity and understanding of the statutes, and shared alignment as to their meaning and how they relate to the foundation’s purpose.

This also leaves us with several questions regarding how statutes should be interpreted under The Foundation Act, and what should be done if board members are incapable of agreeing on their meaning. By giving foundations high discretion and stating that all governance matters are to be determined by a Foundation’s statutes, the law lacks clear mechanisms for resolving interpretive disputes, leaving oversight bodies to intervene mainly in cases of serious or blatant mismanagement. The ongoing conflicts within The Foundation illustrate the complexities artists’ foundations face in honoring (and continuously interpreting) the wishes of deceased artists and their representatives whilst fulfilling its practical needs for preservation. This underscores a broader governance dilemma that may arise in artistic legacies that are often intertwined with familial, commercial—and in this case, spiritual—interests, underscoring the need for clearer frameworks and solutions to reconcile disagreement and ensure cooperative, sustainable stewardship.

Final Thoughts

The ongoing battle within the Hilma af Klint Foundation is not just about governance—it shows how an artist’s legacy, no matter how carefully articulated and planned, remains vulnerable to the interests of those who inherit it. As notoriety and public demand for af Klint’s works continue to grow, so has the intensity of The Foundation’s internal conflicts over how they must manage their legacy. As The Foundation continues to fracture under their ethical and legal dilemmas, it not only jeopardizes future deals, but its ability to fulfill its original mission. Beyond the walls of The Foundation, the outcome of their dispute could set precedents for how foundations and artistic estates how much the board can “interpret” statutes and completely change how the foundation is managed without facing any legal liability. Though current legal developments confirm that the board’s composition remains intact, the conflict is far from resolved, leaving the future of af Klint’s legacy hanging in the balance.

Suggested Readings and Videos:

- Alex Greenberger, Hilma af Klint’s Art Should Be for Everybody—Even if Her Descendants Don’t Think So, ARTnews (Mar. 14, 2025, 12:45 PM).

- Filip Wijkström, Scope, Roles and Visions of Swedish Foundations (SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Business Administration No 2004:20, 2004).

- Guggenheim New York, Hilma af Klint (Oct. 11, 2018).

- Lucas Lockwood Mischler, Artists in Legacy-Land: Endowing Foundations to Balance Market and Philanthropic Activity (Master’s thesis, Sotheby’s Institute of Art, December 2022).

- Kate Kellaway, Hilma af Klint: A Painter Possessed, Guardian (Feb. 21, 2016, 3:30 PM).

About the Author:

Julia Beeson is an LL.M. candidate at The University of Texas School of Law, with a concentration in Business Law. After obtaining a Postgraduate Certification in Art, Business and the Law from Queen Mary University London, and a Bachelor of Arts in Law and Sociology from the University of Kent, she returned to Texas and gained experience working in property tax litigation, consumer protection litigation, and business law.

Sources and References:

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek a consultation with an attorney.