In liberal democracies, we are often told that law is blind to appearance. Yet, the opposite is often true. Public law and policy repeatedly mobilise aesthetic categories—such as decorum, decency, and ugliness—to judge who belongs in public spaces and who should be kept out of sight. These legal deployments of aesthetic norms are not just discretionary or symbolic: they form part of a broader system of exclusion, oppression, and privilege that targets certain groups as unfit to be seen. This is what I call aesthetic humiliation.

Aesthetic humiliation is not about subjective taste or cultural preference. It is a structural mode of misrecognition, through which legal and administrative norms regulate bodies, visibility, and space. By designating some individuals or groups as aesthetically inappropriate – too unsightly, indecorous, or offensive to public sensibility – the law enacts a particular kind of degradation: it communicates that certain bodies pollute the civic order. This symbolic judgment becomes material through policies that marginalise or banish them from public space: Judith Butler’s work on precarity and grievability reminds us how certain bodies are made to appear less valuable, less liveable, and ultimately less visible within dominant frames of recognition. Aesthetic humiliation is thus not only a matter of visual politics; it is a technique of power that reaffirms social hierarchies and legitimates exclusion.

The concept of aesthetic humiliation draws from a broader tradition of critical theory, and calls for a decent society whose institutions do not humiliate its members[1]. When social relations of respect are mediated through humiliating aesthetic standards, the result is not just wounded dignity but compromised agency. Building on this, we should recognise how institutions aesthetically humiliate, and how they embed aesthetic norms into their structures of power and governance.

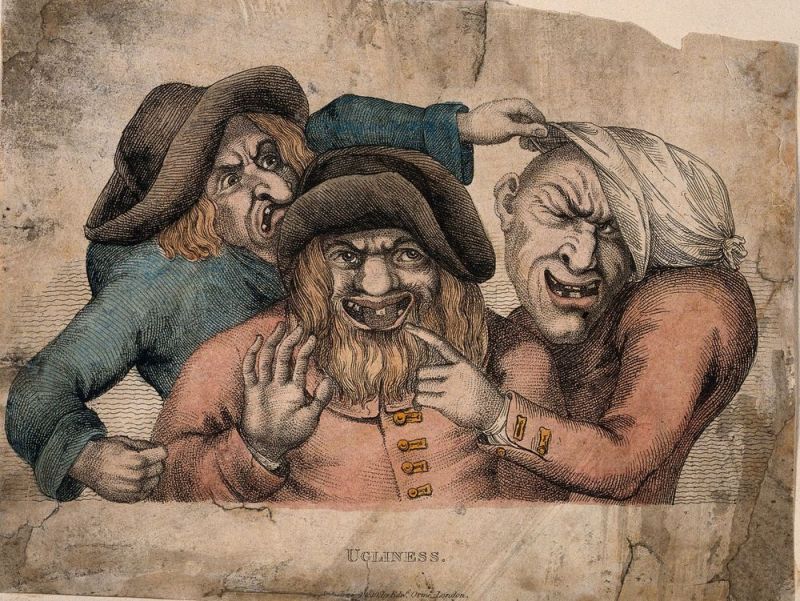

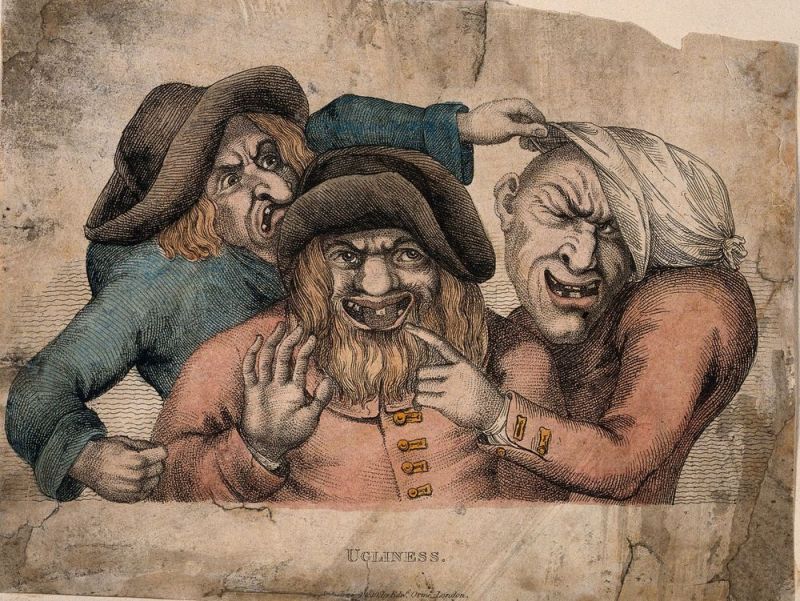

From a legal and political perspective, ugliness has been a sort of receptacle for everything that did and does not correspond to the reference standard for respectability and dignity, depending on the time and place[2]. As a consequence, ugliness can be understood as a “social location complexly embodied.”[3] It is a receptacle for sociocultural feelings and attitudes, thereby producing relevant political, social, and existential consequences: when a body is labeled or understood as “ugly,” a series of social, legal, and political processes are activated explicitly or implicitly, with the goal of excluding or marginalizing subjects. This is the reason why ugliness has been used politically and legally, in a variable interweaving with other categories: gender, race, class, age, ability, sexuality, and body measurements and proportions[4] . The political mechanisms of exclusion, in short, lie at the intersection of these categories and use ugliness as a strategy for exclusion, a stigma that justifies racist, ableist, or ageist policies, as well as all other forms of social and cultural marginalisation. Ugliness becomes a sign of marginalisation, as well as the justification of the necessity to exclude. Those who carry the stigma of ugliness deserve to be excluded from full social integration, the full enjoyment of the privileges (and rights) enjoyed by the elite, by people who on the contrary embody the aesthetic and political canon, what is beautiful, appropriate, functioning, performing, worthy, and decent.

This legal mechanism is not new. So-called “ugly laws,” which proliferated across U.S. cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, explicitly banned individuals who were “unsightly” from appearing in public. In Chicago, a 1881 ordinance read: “Any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object… shall not therein or thereon expose himself to public view.”[5] Though formally repealed decades later, the aesthetic logic of such laws persists in contemporary policies that sanitise public space through codes of appearance and conduct. In many cases, this extends to so-called quality-of-life policing or urban beautification programs, which often disproportionately target those whose bodies, attire, or behaviours deviate from middle-class, able-bodied, and racially dominant norms.

Different and non-normative bodies were at stake, and any manifestations of otherness with respect to a standard order, decorum, and proportion that was set by subjects with greater power and resources. These bodies belonged to poor people, immigrants, people with illnesses or disabilities, injured workers, and people of colour, who were excluded from the sphere of the ‘visible’ and from the horizon of what could be looked at because they were dirty, disabled, deformed, sick, smelly, or simply unsightly. In this vein, ugly laws are examples of how the exclusion of what is perceived as a threat by dominant classes is conveyed by practices of humiliation, at the intersection between an aesthetic category (ugliness) with ableist, racist, classist, and colonialist ideologies. People who are targeted by these laws are marginalised and (often) criminalised not for what they do, how they behave, or what they say, but for their bodies, for the unpleasant sight of bodies reduced to ugly objects[6]. As Schweik rightly pointed out, ugly laws highlight the persistent link between disability and poverty, and the complex intertwining of economic interests, social policies and the construction of the public imagination, at work in the identification of what is ugly and deserving of being hidden[7] .

In modern times, a discriminatory and securitarian orientation marks since the 70s urban policies concerning decorum. Decorum is an elusive category, indeed: originally used in the context of rhetoric, it is gradually being applied in the sphere of social relations to indicate what is appropriate to a certain place or person, and what is appropriate to it because of its position, nature, role, function, and so on. However, when used to discipline public spaces, policies concerning decorum merge “zero-tolerance” claims with an explicitly aesthetic approach. City administrations, especially when concerned with touristic or privileged areas, explicitly used the argument of decorum to justify measures aimed at social control[8], for instance targeting some (licit) behaviors as indecorous.

As some scholars rightly noted[9], a decent city is a city where misery and marginality are unseen, where germs and bacteria-carrying contagion are identified in people belonging to minorities (such as Roma and Sinti), beggars, squeegee men, street vendors, and prostitutes, as well as in the proliferation of ‘ethnic’ food shops. Groups targeted by these policies offend the aesthetic sense of decency shared by the majority of the population, or the part of the population that is in positions of privilege, and are sometimes perceived as harassing by their very attitude or posture. Decent cities sweep the dust under the carpet, but the dust is made of people, and often vulnerable people.

For instance, in many European cities, ordinances prohibit begging or sleeping in public not because these acts are inherently criminal, but because they are seen to offend the visual sensibilities of tourists or affluent residents. In Florence, Italy, a local order banned street performers and beggars who used animals, thereby simulating a state of necessity and provoking an unmotivated feeling of pity. In Rome and Milan, settlements of Roma and Sinti people have been forcibly evicted from semi-peripheral camps, often without warning or due process, under the justification of maintaining urban decorum. These individuals are frequently cast as out of place, not for what they do, but for what they appear to be – their mere presence is perceived as degrading the aesthetic order. As such, aesthetic categories become a means of criminalising visibility itself, rendering certain bodies incompatible with the visual expectations of public space.

What is crucial here is that aesthetic humiliation is often directed not at isolated individuals but at social groups – disabled people, racialised others, gender-nonconforming individuals, the poor – who are constructed as aesthetically deviant or contaminating. Aesthetic misrecognition thus operates as a collective form of symbolic violence, constituting what can be named group vulnerability: a structural condition in which entire categories of people are made to bear the burden of aesthetic judgment, and in doing so, are systematically denied equal standing in public life.

This kind of group-based exclusion cannot be reduced to isolated incidents of prejudice or bad policy. Rather, it reflects a patterned deployment of aesthetic codes as mechanisms of regulation. From the colour and style of clothing to bodily posture and perceived hygiene, aesthetic norms shape how individuals are evaluated in public. These evaluations are not merely social, as the examples demonstrate, they have often legal value, determining access to services, freedom of movement, and even protection under the law.

Moreover, aesthetic judgments have affective force. They produce and reinforce emotions – disgust, revulsion, shame, fear – that legitimate exclusion. The presence of certain bodies becomes linked to discomfort or disorder, triggering a demand for removal in the name of public order. In this way, aesthetic categories function as affective filters, organising the space of appearance and determining who is allowed to inhabit it without scrutiny or sanction.

To dismiss this as symbolic politics would be to miss the point. Aesthetic norms shape who is seen and heard, who is granted rights and space, and who is policed or disappeared. They also structure affective responses that rationalise further marginalisation. In this sense, aesthetic norms do not merely reflect social values; they organise them, codify them, and weaponise them.

But where there is degradation, there can also be resistance. Groups targeted by aesthetic humiliation have increasingly mobilised counter-aesthetic strategies: refusing invisibility, reclaiming stigmatised appearances, or producing alternative forms of collective presence. This is what Nancy Fraser described as the work of “subaltern counterpublics”: arenas where marginalised groups generate oppositional discourse and reframe the dominant aesthetic-political order[10].

Examples abound: fat activism and the politics of visibility; disabled artists confronting norms of bodily form; feminist and queer collectives that celebrate what hegemonic aesthetics would cast as improper or excessive. These practices are not merely cultural. They are political acts of re-signification, aimed at unsettling the visual order that justifies exclusion. They confront the very terms through which bodies are judged, classified, and ruled. They also expose the complicity of legal frameworks in sustaining these norms, and open up new possibilities for reimagining public life in more inclusive, pluralistic terms.

To critically engage with law today means to take these aesthetic dimensions seriously – not simply as matters of cultural taste or symbolic regulation, but as part of the material architecture of systemic injustice. Aesthetic humiliation is one of the quiet operations of legal power: less visible than overt discrimination, but no less effective in constituting who gets to appear in public, and who must remain hidden.

If we are to take seriously the objective of justice, as well as of a decent society, we must challenge not only what the law says, but what the law spotlights, and what it hides and renders invisible.

[1] Avishai Margalit, The decent society (Harvard University Press, 2009); Id., “Decent Equality and Freedom: A Postscript”, Social Research 64, No. 1, The Decent Society (1997): 151-152; Susan Miller, Shame in context (Routledge, 2013).

[2] Greta Olson, Criminals as animals from Shakespeare to Lombroso. Vol. 8 (Walter de Gruyter, 2013).

[3] Tobin Siebers, Disability Theory (University of Michigan Press, 2008), 14.

[4] Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, “Ugliness,” in Critical Terms for Art History, ed. Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff, University of Chicago Press, (2003): 281.

[5] Chicago City Code 1881: see Susan Schweik, The Ugly Laws: disability in public (New York University Press, 2009), 9.

[6] Nöel Carroll, “Ethnicity, Race, and Monstrosity: The Rhetorics of Horror and Humour,” in Beauty Matters, ed. Peg Zeglin Brand (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000), 52.

[7] Schweik, The ugly laws, 63.

[8] Valerio Nitrato Izzo, “Law and hostile design in the city: Imposing decorum and visibility regimes in the urban environment.” Oñati Socio-Legal Series 12.3 (2022): 522-539; Rezafar, Azadeh, and Sevkiye Sence Turk. “Proposing a checklist for aesthetic control and management in a city under neo-liberal influences: Istanbul case.” Open House International 47.1 (2022): 68-86.

[9] Tamar Pitch, Contro il decoro. L’uso politico della pubblica decenza (Against decorum. The political use of public decency) Laterza 2013, ch. 3.14 Kindle.

[10] Nancy Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere: a Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy”, Social Text, (1990) 25/26: 56-80.